Seafoam Dreams

Ch1

The quiet man did not want to sleep, out of fear that he’d dream. He knew it was the only thing he could do. He rumbled and spun and had no peace. Neither side of the pillow was cool, and soon, sweat was dripping down his brow, but he could not escape the peace of his weighted blanket. He cast the ever warm pillow as far from him as he could – though there was only so far from him it could be, given the confines of his claustrophobic apartment – and soon, he was using his arm as a pillow, folded under his head. He was no cooler nor more comfortable, and he knew that come morning, his arm and neck would be struck with soreness.

Not like I’ll be using them much anyway. It’ll suck, though.

Not but one roll and attempt at mental peace later, he slipped fitfully into unconsciousness.

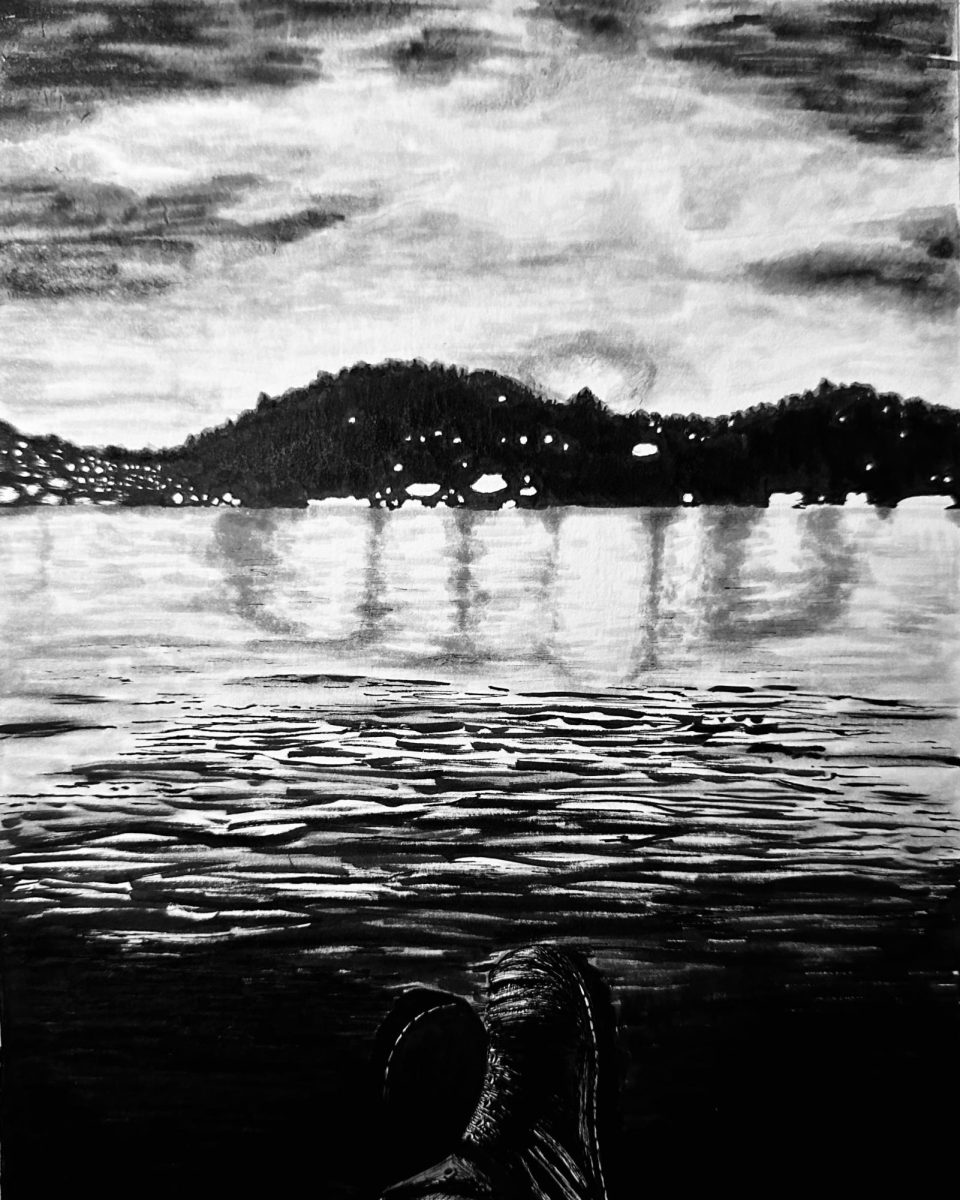

A rumbling emanated from a point just 10 feet away. A rumbling that shook him to his very core. It seemed so loud, that it must stretch from horizon to horizon, that it must be all encompassing and everlasting. The ground below, green and verdant, sped past. A leaf, tiny in the vastness of the jungle below, shook, by wind or concussion of noise. Then, the green faded to gold, a frothy white, a pale light blue, then a deep, effervescent, cerulean. The rumbling only seemed to grow louder. There were swirls in the water. They had always reminded him of a Japanese print.

The rumbling was reaching fever pitch. The end of the dream was nearing.

He tried to breathe in, or out, or move anything at all. He always did, right about now. It didn’t work. It never worked. Nothing would move, nothing that was corporeally him, or part of the machine hoisting him so high.

The rumbling was almost painful now, and getting hard to ignore. It beat him over the head and ears with an oar until it splintered. It would seem to dim a little, promising salvation, before redoubling, and casting him low again. It never ended. It never ceased. It was everything, and always, and always would be. There was no escaping.

He bolted upright, sending sweat from his brow flying across the room.

“Tshieeeeet. Ugh.”

He locked eyes with the japanese print hanging by the foot of his bed. In his mind, the scene was replaying again. The leaf, the beach. The sound. He committed it to memory. It was the same every time – among others, it seemed to join him every night or so – but still he tried to save it. He turned, so that he faced the side of his bed, and scooted so that his back rested against the cool wall.

Covering the walls of his apartment were a small selection of other Japanese prints, though none grabbed him as much as one hung by the foot of his bed. Other than that, there were a few posters of old sailing ships, recreations of old propaganda declaring that one nation ruled the waves, or had the newest, biggest, baddest boat. There were also more modern posters, one labelled “Victory”, one “Constitution”, and one “Vasa”.

None of the naval posters had quite what he was looking for, though the Vasa poster came the closest.

He also had posters for caves, spelunking, famous coastlines, plane tours, common jungle flora, and even the fluorescence of water. His walls were inundated with posters of one matter or another.

Below them sat the rest of his world. A small fridge, an old stove past its expiration date, two ventilation ducts, one bed, one bureau for linens and clothes, and a small desk, with two drawers. Plus, there were five small drawers in various places, two cabinets low down, four high up, a couch, a washing machine, and a bathroom barely worth mentioning.

He coughed into his elbow, before pushing himself forward from his perch high on his bed. His feet hit the linoleum floor with a muted thud. He stumbled a little bit, but not enough to fall over. He padded over to his fridge, and pulled it open.

One box of broccoli, three mouldy figs, one mostly empty half gallon of milk, one completely empty box of orange juice, no pulp. Half of a carrot, overcooked noodles in a ziplock.

Not much, huh.

The fridge door swooped shut, and he was left in the dark again. The ice maker whirred and crackled, and the air conditioner hummed in the distance; other than these, he had silence. He padded over to the bureau and yanked out a white t-shirt, and black sweats. He grabbed his phone, and walked to the door. He reached for the worn brass handle, but stopped and leaned forward, resting his head against the soft wood. He waited for a bit, fidgeting with the lock, brow furrowed. Eventually, he stepped back, and opened the door.

Outside was a long hallway, lit with dim – but very efficient, he was told! – LED lights, one of which was flickering. On each side were doors innumerable. Though some creaked while others did not, and some had unseemly damages, scrapes, or scratches, they were all really identical, save for the mats at their feet. Some were funny, sassy, or bland as heatstroke on a sunny day.

At his own door’s foot, there was nothing. Across from his door rested another identical door, though he would always say that this door was just a bit glossier, just a bit brighter, just a bit more wood coloured. At its foot sat a doormat reading “welcome to the jungle!”, and the outline of a lunging housecat.

There was one window at each end of the hall, barely perceptible at such a distance. One of them was right up against a neighbouring building, and showed nothing. The other sometimes let in some natural light. It let none in now.

He walked across the hall. The doormat was wet, probably from rain sloughing off of a coat. He knocked on the bright door. There was a light thud. A few moments later, a small voice came from within.

“Al?”

He opened his mouth to respond, but found his voice caught in his throat. He cleared it.

“Yeah.”

“Come in, please.”

He walked in, and she followed. There was a wet coat hanging by the door, an old fashioned, brown-grey trench coat. It always reminded him of old detective stories.

The walls were far more tastefully decorated than Al’s. There were two nature scenes of no particular note, and one abstract painting, composed of blocks and stripes of red and blue and yellow. There was also a couch, a loveseat, and a small bed, similar to Al’s. Other than that, their apartments were identical.

They each found seats, Al on the couch, and the woman on the loveseat.

Her straight black hair caught and pooled on the chair behind her head.

On the counter sat a mostly empty coffee cup, and there was a bag of groceries on the floor, yet to be put away.

That’s where she was most comfortable, on the loveseat, with her knees to her chest. The thought made Al feel a little lonely. It was cold.

Al was warm, though. Her apartment was really the only room he wasn’t too warm in. She kept it cold for him, though she’d never admit it. She blamed it on faulty hardware, but changed the subject whenever a conversation turned to fixing it. She wasn’t home enough for it to bother her much, though; after getting home, she usually just ate, then fell to the task of sleeping through the sunlight hours.

Al cleared his throat.

“I, uh, couldn’t sleep again.”

“How bad was it?”

“I don’t know about bad. It was vivid though; Really vivid. Maybe the most it’s ever been, or maybe not.”

She squinted at him, and shook her head a little.

“Or maybe not?”

He shrugged.

“It was vivid.”

“Have you talked to your mum recently? I bet she’d love to hear from you. Or your dad?”

“No, I haven’t been-” He stopped.

“Al? You haven’t been, what?” She cocked her head a little.

“I haven’t been able.” It was almost a whisper.

“Oh Al.” She unfolded and walked over to him. She pulled herself up onto the arm of his chair; it was really only big enough for one, but she didn’t intend to let that stop her. Perched as she was, she leaned over, resting her head on his. They appreciated each other’s presence for a while. They let the sound of someone else’s heartbeat, the steady rhythm of breath and gentle, vital heat buoy them against the worst.

After a while he forced himself up. He shivered a little bit in the cold, and coughed.

“I’m gonna… I should go try again.”

“Could luck; good night.”

“Good night. And thank you, Sophie, for everything. Really, I mean it.”

She cracked a sad smile. He did too, the two of them enjoying some little joke only they got to cry to.

“Of course, Al. Always.”

“Good night.”

“Good night.”

He turned and stepped into the hallway. With a soft, whispered click, and shut the door. Sophie turned away from the now closed door. The world was a little bluer, but also a little brighter. She put away her groceries, drank a glass of water, brushed her hair, brushed her teeth, and paced for a while, before heading to bed.

Al walked into his own room. He felt a bit lighter now. He stared at his posters for a while, paced a bit, and lit a candle just to blow it out, before heading to bed.

At the same time, in their little rooms on either side of a long hallway, Al with his posters and Sophie with her nature scenes, just as the first signs of light were peeking over the horizon, they both slipped into a deep, calm sleep.

Ch2

A car rushed by. The wind reached out and brushed the hair from Al’s face. For a brief moment, he could see the entire scene: the leaning buildings, roads not crooked but not straight. There was a pub, overfull, sloshing with people. The chatter from the pub’s inhabitants washed over him, filling his ears. In the distance, on the other side of the road, a bright red shop stuck out. It was unclear what they sold; out front sat a map, a flag, three snowglobes, four and a half pairs of shoes, and a rack of sunglasses.

Then his hair settled back down, and he was left with only enough vision to not trip into traffic. He preferred not to trip into traffic; it seemed a sad way to die.

He felt the shock of the steps reverberate through him. The wind blew, then howled. A newspaper flew by. His hair rose again; the red store caught his eye again. What could be in there? It seemed like there could be anything. There weren’t any cars coming for a while, and he could barely remember why he was there anyway. It wouldn’t take much time to visit.

He crossed the road in a light jog.

Soon, the red door swung open, and a wave of warm air rolled over him. A little bell rang out. A sign swung by the door, light grey with swirly, black writing: “family owned, locally dedicated!”. The store smelled a little bit like cinnamon and incense and dust, and something sour he couldn’t identify. The floor was covered in curly, brown-grey carpet. Posters lined the walls. Posters of all sorts: Japanese prints and naval matters, resembling his own, but also so much more. There were political posters, comics, posters about celebrities, posters with jokes. There were posters that looked to have been stripped from an intersection, and one from a Turkish airport.

In the middle of the store, there was a rack of socks of many colours and patterns. In the back, a wooden desk, dark and ornate, stood in contrast to the store around it. At the desk sat a woman with straight, shoulder length hair of a dark brown hue. Round glasses sat on her face, as brown as her hair, and through them she read a book, a fiction novel that appeared of a medium length, like her hair. She didn’t look up when he walked in; in fact, she hardly seemed to notice.

There were also a number of books throughout the store, a microcosmically eclectic mix. Al picked one up, with a red cover and upstanding, honest writing. Not very swirly at all. He thumbed through it for a moment, feeling the parchment, and the sharp edge of the page. It reminded him of the posters in his room. In fact, he could probably fill a small book with them. A cloud of dust flew up as he dropped the book the last couple inches back onto its stack.

He meandered further and further into the shop. Soon, there was scarcely any natural light; the store was deceptively deep. He felt waist deep in little figurines, big figurines, teapots, plastic jack-o-lanterns, and flags. It felt mysterious, and enchanting, and brought a silly little smile to the corners of his mouth. His head bumped a dreamcatcher, sending sparkles of light from a nearby lamp dancing across the far wall. One of them caught the employee in the eye, and she flinched.

She looked up, and appeared to notice him for the first time.

“Oh, hello. Can I help you find anything in particular?” Without looking, she slid a bookmark onto her book and closed it with a fwump, sliding it over to the side as she did. The book almost hit a quill, but just barely missed it. It appeared a practised manoeuvre; he wondered if the quill contained any ink, or if it was just for display.

“Ah, not really looking for anything in particular. Just looking around at…” he gestured vaguely to the deceptive immensity of the shop before him. It seemed to be daring him to describe it. He looked back at her with a forced smile. She waited for him to finish his sentence. He, unfortunately, had nothing with which to finish it, and had not particularly intended to do so from the start. She was catching on to this, and simultaneously, he was catching on that she was catching on, even though he had thought it had already been conveyed by the gesture.

There was a long beat of silence as they stared at each other.

It was very awkward.

“All right, tell me if you need anything.”

“Will do.”

He attempted to put a pile of dolls from the eighties between him and her. He silently brought a pen out of his pocket and clicked it open, before flipped it over his thumb twice, and clicking it shut. He repeated that several times before pocketing it again, and taking a deep breath. The cinnamon smell was stronger now, he could almost taste it. The air seemed to push on the bottom of his lungs, and he coughed suddenly.

Ahead of him was a rack of postcards from various places throughout the world. Some appeared worn, and some brand new. He moseyed over absentmindedly, still recovering from his failed attempt at conversation. His foot tapped quickly on the carpet. There was one from Paris, one from Amsterdam, New Orleans, Seattle, Mexico City. His eyes glazed over at Berlin, when abruptly his foot stopped tapping. His breath quickened, and his heartbeat followed shortly. His eyes were locked on one postcard, perhaps the most worn one on the shelf. It had a picture of a fluorescent body of water, with walls and roof of stone, overlapped with bold yellow text reading “Come visit us at the Saint-Léonard underground lake!”. Again, he pulled out his pen, click, flip. Click, flip. With a shaky hand, he reached out, and picked up the postcard. The pen went away. He felt the smooth, waxed paper under his fingers. It smelled of fuel, and herbs, and the heat of the sun. It smelled like it had seen the world over. He flipped it over. He walked over to the cash register, entranced. Hardly ever breaking eye contact with the postcard, he paid, and wandered outside.

He blinked. It was brighter out than when he had entered the store. The cold nibbled at his cheeks and set his eyes to watering. Wiping them away, he looked around. The pub had emptied some, and a light frost had made itself apparent, coating the ceilings and balconies around him. He shivered, and took a deep breath, holding himself back from another coughing fit. He hadn’t realised he had been holding it in. He allowed the cool air to fill his lungs, letting the icy zephyr refresh him. The postcard, now in his pocket, weighed heavily on his mind. Unsure of what to do next, he turned and headed in the direction of his apartment. He had had a task initially, but now it was as if the only reason he had ever left his home was to find this red store. More importantly than the store, though, was what had been in the store. The postcard.

He turned, and began walking.

The postcard was sitting on his mind, like a helmet that could not be removed.

He tried to let his mind wander, allow his eyes to disconnect from his mind, and his sentience retreat into his skull, and allow the helmet to slip off his head. He focused on the concrete, on the details of him that made him, him.

His nose, fingers, ears and toes all tingled in the cold. There was a pressure at the bottom of his lungs. A brief inspection of his fingers brought him to the hypothesis that all four extremities were a similar shade of bright red. A shallow ringing overshadowed the sounds of life around him, those of cars, people, people in cars, people in cars in puddles, people in apartments, and all the other mundanities that made a city.

He wiped away a moisture that had formed under his right nostril. Staring at the back of his hand, he watched the moisture dry, and disappear. He admired the creases in his hand, the folds and hollows of skin, where it stretched and squeezed, crinkled and smoothed. No matter how realistic his dreams got, no matter how many notes he took afterwards, they could never truly match the real thing.

He looked up, and again gasped lightly. Another thing sat before him that could not be properly replicated in a dream. A detailed cityscape, laid bare to the purveyor’s whims. A harsh light showed the city of London in a surreal frame, brought to life by the provision of a shallow hill, peaking on the outskirts of the displayed city, and allowing an attentive pedestrian an unmatched view.

By the benevolence of some city planner’s foresight, there was a wooden bench overlooking the view from behind a black wrought iron fence, tastefully ornate. Under the bench sat a dedication to someone Al had never heard of, and had never had the will nor particularly the desire to look up. He had always found the bench a little sad, but had appreciated the view in its care many times before.

Today, there was someone else at the bench, sat on the right side with back straight, one arm propped on the armrest. They had straight black hair, the length of which was concealed by the collar of a brown trenchcoat, raised against the wind. Al knew it to be roughly to the shoulder, though. He walked up behind her.

“What are you doing out here?”

She jumped, and brought one hand to her collar, taking a deep breath, and turned towards him. Reassured, she laughed a little bit. Al joined her.

“My god Al, you scared me.” She turned back towards the view, and crossed her legs.

“I couldn’t sleep. Something kept me up.”

“Yeah.” He walked around the bench, and sat on the left side, his back mimicking her’s in its straightness. He crossed his legs, and folded his hands on his lap.

“Any ideas what it was? Could it be the cold? You should really get that fixed.”

“Maybe I should. How was your walk?”

“Nice, I got this.” Al reached into his pocket, and retrieved the post card that had been weighing so heavily on his mind. At the same moment, a snowflake landed on the back of the bench. He held a hand over the postcard to protect it from the snow, and handed it to Sophie.

She took it, taking care to hold a hand above it protectively. Al noticed that her hand appeared remarkably pale. The skin on the side of her nails facing her thumbs had turned white, killed from incessant fidgeting.

“Is this- is this what it looks like?”

“Not exactly.” He swallowed. “But pretty close. For me it’s taller, and wider, and altogether larger. Plus, obviously,” he cupped his hands as if to hold a water, then moved them apart, as if attempting to sign “banana” to a deaf person, but misinterpreting the scale of the motion.

She nodded.

“Yeah.”

The conversation petered off into silence. They each appreciated the view. Thoughts of the postcard, of dreams, of the events of the day, the store, and the sudden change of weather rattled around in Al’s mind.

Sophie just enjoyed the view.

Ch3

Al was back in his room, sitting at his desk. His foot was tapping against one of its legs.

Tap tap tap

On the desk sat a notebook two thirds full, one third empty. He was writing, relating to a future reader his thoughts on various topics, whatever came to mind. It often returned to dreams.

Tap tap tap

The sound of the tapping, the scribbling, and the turning of pages found rough parity with the sound of his thoughts; his attention would drift back and forth between the two, so that sometimes he would write intently, with a careful idea of the placement of each sentence, word, stroke, concept, and other times words would appear on the pages seemingly at their own volition, or otherwise randomly, and of no apparent volition whatsoever.

Tap tap tap

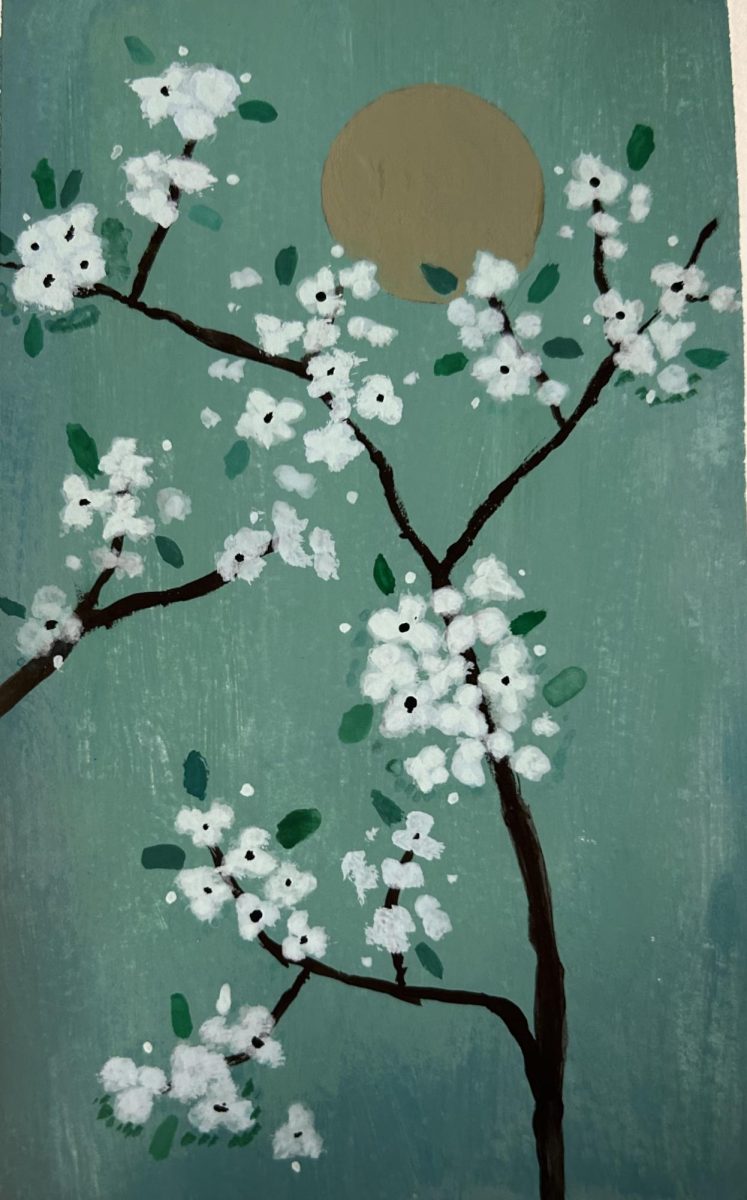

The notebook was the length and height of a sheet of paper, dominantly black, with a pattern of flowers weaving its way up the spine like a braid, spilling onto the front and back as it did. It had no text on any face, and he preferred it that way. The text was meant to be inside the notebook, not displayed on its exterior.

Tap tap tap

He was writing with a quill rather than a conventional pen, it being one of his prized possessions. He hated the idea of writing with anything else; he also hated the idea of it sustaining any sort of damage or wear.

Tap tap tap

He reached the end of a page, and flipped to the next. The nib of the quill moved to the top of the page, before pausing. He admired the feather of the quill in the light. It was black, with a stripe of white running down the centre, from tip to nib. He rotated it, watching the light move back and forth across its shiny surface. He sighed.

Tap tap.

He flipped the book shut, and returned the quill to its pen holder. He slid the left desk drawer open, and put the notebook back in. He shut the drawer again with a sharp clack. The right drawer had a lock, and though he didn’t test it, he knew that it was secure. He leaned back in his chair, stretching. The tapping of his feet had stopped. He arched his spine over the back of his chair, and craned his neck, staring at the ceiling. He studied in detail the particular shape of the drywall. It’s every nook and cranny, its facets and crenulations became the subject of his fascination.

Rain was pattering against the window, covered by wide white blinds. If the blinds had become transparent, he would have seen the telltale signs of a sunrise; people getting themselves to work, people working, people who’d worked returning home. Similar in appearance to a sunset, though the variance of light was quite inverse.

It was all the same to him, though.

Behind him, his bed appeared to have been rescued from a disaster zone. The orientation of the sheets and blanket had no clear relationship to the bed, and the pool of sweat on the bed spoke of a night of attempted sleep.

In actuality, he had dreamed again. The same dream, with the plane, the leaf, the coast and the water. It had woken him once again, and he had risen, as before. This time hadn’t disturbed Sophie, though he suspected she had gotten home by then. Instead, he sat down promptly, and began writing. It had not appeared an appealing concept the other night, but that morning he would have rather been nowhere else.

As it often did, his dreams featured prominently in his writing. He detailed them exactly as he remembered them, without any embellishment worth speaking of. He did it to bring himself a measure of peace about what he could not explain. This happened to be most things, so there were many other topics in his writings as well.

He reached down, re-opened the left drawer, and pulled out a different notebook. There were several others in the drawer, though they appeared significantly used, and perhaps only kept around for the sake of sentimentality.

This new notebook was red, with a black brand name on the front. He had tried to cover the name in red marker, but had found that the marker colour was far too far from the natural red colour of the notebook, and only proved more distracting. It wouldn’t adhere to the waxy surface, anyway. In contrast to the other notebooks, this one was ring-bound. He favoured ring-bound, but found that in the vast majority of cases the disruption to the clean geometry of the notebook (allowing for easy stacking) was severely disrupted, a tradeoff he was not willing to make. In this case, though, he made an exception.

He attained a pen from his drawer – a generic one, this time – and opened the notebook. Inside were a few notes on characters, themes, scene ideas, symbols, and all the rest of the framework he deemed necessary for a meaningful book, effective in its goals. It was his first, and a very long term project, at least on the scale of a man. He had been working on it in some fashion for as long as he could remember, though that had most often taken the form of idle speculation rather than writing- indeed, if he had spent all the time he had used to think about the book instead with a notebook in front of him, and pen in hand, or even if he could use all the time he had spent with a notebook in front of him and pen in hand instead applying the instrument to the page, then he would certainly by now have achieved literary fame.

Such speculation aside, the same issues he had always met with, met with him now. He could not think in detail, he did not know what would happen. One interaction was too stale, one was unrealistically dramatic.

Tap tap tap

“Mnnugh.” He replaced the notebook and pen back in the drawer and stood, pushed in his chair, took three deep sips of cold water, undressed, and got back in bed. He could not then write, and didn’t wish to read, so the next best option would be to try and sleep, rest his addled mind, and hope that upon waking, he would be more amenable to one of the options before him.

—

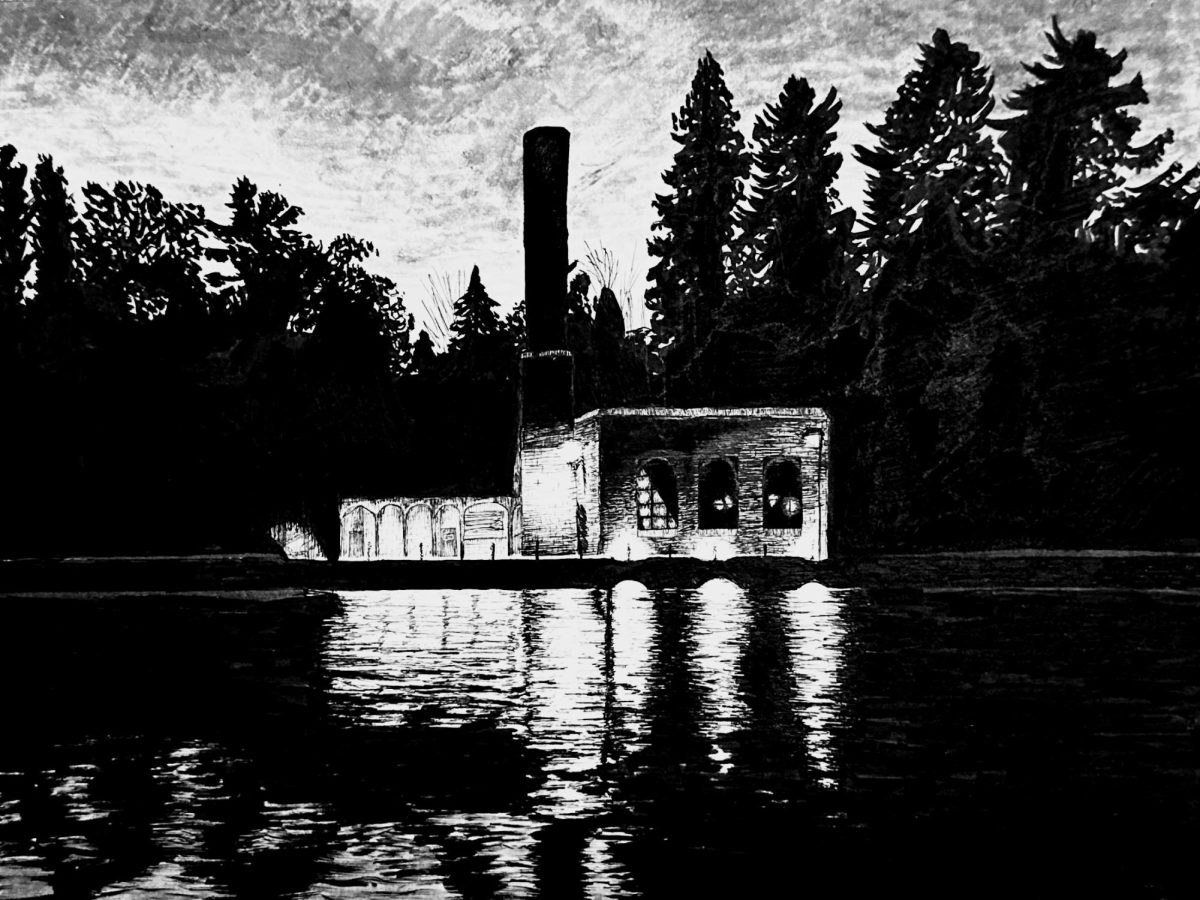

The first thing he noticed was the slow swish of the waves against the distant shore. They calmed him a bit, but they were wrong, deeply wrong in some way he could not place. Above him, great furled sails cut through a sky, itself hidden by a cave roof, as if by a knife or talon; there also appeared great trunks, alongside a vast tangle of reeds and vines to hold them up. When he tapped his foot, there was a hollow wooden tthump, tthump, tthump. The world swayed lightly on intangible winds. It smelled salty, and wet, and damp, and vital. It seemed a forest had been flooded, drained, and petrified.

Next, he realised he was on the deck of a ship. That explained the swaying, the hollow wooden tthump, the sails, the trunks, reeds, and vines – indeed, masts and rigging. It was the same ship every time, with the same tall forecastle and aftercastle (as he had learned they were called, for this very reason), narrow beam with long, elegant lines, supplemented with an aggressive gnashing predator of time kind carved into the bowsprit. However, it did not explain its presence in a vast cave, with no apparent entrance or exit of any kind. Neither was there any visible source of light – it was lit only by the virtue of, well, if it was not, how would he see?

Next was the vastness of the cave. He let his eyes wander, and saw that the cave had an end only in the sense that a mountain had an end when one was in the earth’s heart’s left ventricle, or the sense that an ocean had an end when one was drowning at sea. No entrances, no exits, only the roil of the waves, their breadth breaking on the shore, and the uncanny sense that a texture had been applied to an object too large for it. Out of the corner of his eye, he could have sworn there was a repeating pattern in the rock face, but he could never identify it if he focused on it.

A low whistling that he hadn’t been aware of up until now – though now he realised it had been there the entire time – began to increase in pitch and volume. Soon, it seemed as large as the cavern; despite its enormity, he found it oddly calming. It soothed him, like salve on a burn, or water over scorched timbers. The sound, he’d realised, was caused by the rush of the wind through the rigging. He’d then put together that its increasing ferocity indicated that the wind was picking up. A new sound joined the hissing; the sound of canvas and rope rubbing against each other.

It was not by accident, nor an idle swaying in the wind; the immense sails all unfurled, all at once, as if the ropes holding them together had been cut by one great stroke of the wind. A brush of new wind sent his hair flaying. Above him, a new sky; mammoth white fields, occupied by cattle of shadow, and expelled dust.

A moment later, the sails caught the wind, and with a jolt, the great ship began to move.

It was unsettling. It did not seem right for such a thing to move, nor for such a thing to float, truly. It felt right for it to sink, perhaps for it to sink with him on it. If that’s what it took to make the world right, then that’s what it took, and who was he to say that what was ordained was falsely so.

It was picking up speed quickly now, a truly strange sight; an ancient, leviathan ship, imposing in its own right, darting with such vigour, rendered truly insignificant before an ancient, leviathan cave.

It was wrong.

It was all wrong.

The weather was picking up; the water had been a placid pool, like a pond on a warm day. Now it was moderately active, with waves a couple feet tall. The wind kept rising, the whistling ever heightening in pitch. The bow and stern were see-sawing up and down now; the entire ship pitched like a pendulum moving along a rail. The ship was heeling, kneeling before the might of the wind. He didn’t see it, but he knew that a wake was rippling out behind the ship, and a fountain of spray rose where its nose met the water. It never occurred to him to check if these were the case, they simply stood as evident.

The wind was tearing at him now, and the ship seemed to be trying to buck him off. He kneeled on the deck, and gathered cannonballs in his arms to stay tethered to the only earth he then knew. In fact, cannonballs and powder charges littered the deck, and a number of cannons peered through the gunwale. He again realised that, though he had not consciously registered their presence, they had been there the entire time.

He felt a cool wetness on the back of his neck, and in his shirt, causing it to cling to him, much as he clung to the ship. He could not tell if it was from surf, or from the rain that, though he could not see it, he knew was pouring down over the entire ship, from swollen, furious storm clouds unseen.

The overwhelming wind and impossible rain, the pitching and rolling and bucking of the ship, the thunder of the surf, it was all too much. He could not stand to exist.

He withdrew into himself. He attempted to shield his mind from the world with skin unfeeling, and glassy eyes unseeing. He felt the coolness of the round steel balls in his grasp, he felt the chill of the wind running over his sodden back, the prickles of goosebumps running down his spine. He felt the desperation to escape, he tasted the need for sun, for freedom, to sink into the deck of the ship and be held one last time. He rebelled against the sea, and the waves, and the impossible rain and the wind unending. He rebelled, but he knew he rebelled for naught, for he was caught in the battle between two ancient things, and the only thing that remained for him was doom, and despair, and a warm, cold, rocky grave. The wind reached a fever pitch, the waves shook his very existence.

A Crack, dwarfing every sound and sensation of the entire miserable journey. It sent a shock through the ship, through the wind, and into the water. The screeching of the wind dropped by half, and the ship seemed to slow its endless progress through the water. It seemed to mirror his thought, his rebellion. He knew the ship knew it was inevitable. There would be no happy ending for it. As the ship reached the next great wave’s crest, and slowly, slowly pitched down into the trough, gaining speed through the air, it spun. The bow went left, and the stern spun out to the right. It spun, and when it reached the trough it slammed into the water, ceasing all momentum.

Some minor fault in the wood of some spar or mast, some tiny seed of rot, or deficiency of the trunk from which it was so meticulously extracted, had proven enough, to prove the ship, and its single occupant, not enough. The endless cave, and the water, and wind, and waves and rain had said “You fucking dare? You wish to match my might? You really think yourself so able, so strong as to stand against me?”

And they had, and they had but they were not.

And now, their broadside to the unstoppable tide, a wave rose before them, ship and man, like a great kraken from the deep, come to extract its harvest. It rose, but instead of pitching they rolled, and rolled, and rose along the wave and rolled, and soon there was more water than cave roof above them. As the cannonballs in his grasp began to slip down into the surf, he screamed one final scream of desperate rebellion, before sinking into the frozen, icy waves, and then he was no more.

—

He bolted upright; his bed felt as wet as the icy sea. He coughed mightily, as if his lungs were trying to dispel the cave’s sea from his lungs. He threw off his blanket and sheets, and swung his legs over the side of his bed. He stood, dressed, stared for a moment at the locked drawer, before pulling out his writing notebook, quill, and beginning to write.

—

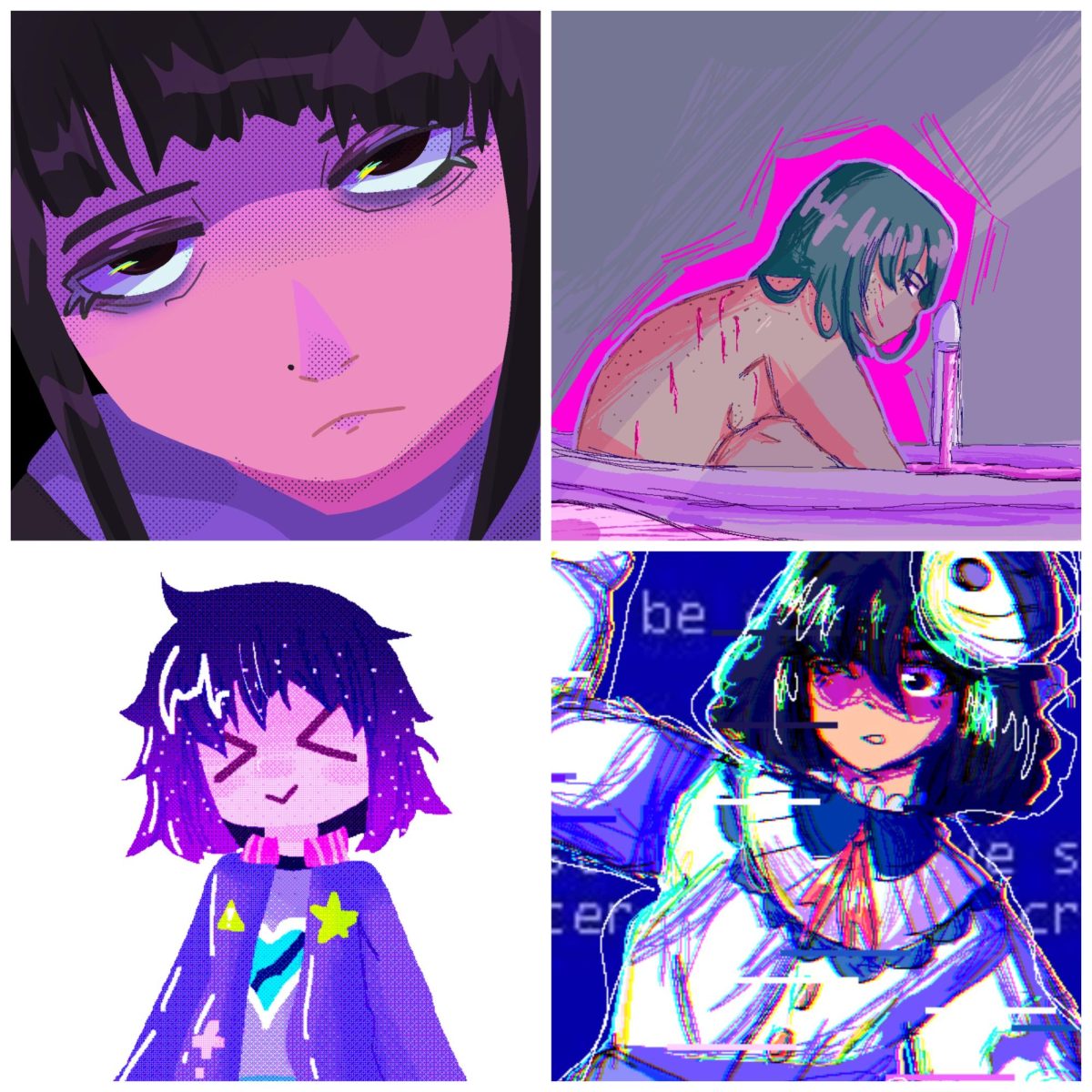

Al sat on the same big, soft couch in Sophie’s room. His head was resting on a closed fist attached to his left arm. Though his eyes were open, his brain slept, and few thoughts crossed his mind. His eyes followed the swirls of snow, floating through the wind’s currents and eddies. He had had the same dream before, but never so strongly, so intensely, so real-ly. He could see the shore and deck and straining hull of the ship in the shape of the window and the road beneath. The depth of dark seemed identical to the nooks and crannies of the walls of the unending cave. He had begun writing. It was momentous, the first true steps of a project he had long been pining at from a distance. That vivid, real-fake scene of the ship and surf had taken him utterly. It had swamped him, like the great waves over the side of the ship. He had felt the drive to do naught but write since then.

A cursory research told him that many great writers wrote pitifully little per day, and only accomplished their greatest works through titanic dedication, and the virtue of already being rich. Al was not having the same experience. The urge to write had ripped through him like a fever. Sophie had had to stage an intervention to prevent him from typing himself to the death where he sat.

Clink Clink

Behind his turned head, on a low coffee table, sat a steaming, untouched, mug of something warm and dark, a deep amber colour like the edge of a honeybee’s eye. Further behind him, once again on the loveseat sat Sophie, stirring her respective beverage. Her spoon was small and metal, the colour of a european starling viewed in a mirror. It shone, and a reflection rippled across it. If Al had been looking, it would have reminded him of the light reflected across the surface of the waves.

He was not looking, so it did not.

“Do you think it was the postcard?” Al jumped as if startled. “I mean, that’s the only thing I can think of. It was pretty soon before, so…?”

“Maybe. It was soon before, so that would figure. I’ve no other ideas, anyway. Not that I mind. It’s good to finally be writing.”

“Yeah.” She sounded unconvinced. She sipped her tea, but only lightly, before coming to the conclusion that it was not yet ready, and continuing to stir. She seemed to fortify herself.

“I’m excited for you Al, I really am. It’s fantastic that you’ve begun writing, I know how much that means to you.” Al finally stopped looking out the window at the snow spinning by, and turned his head partially towards her. She continued. “I know it’s been a long time in the works, and it’s great that it’s finally being realised. But Al, you can’t kill yourself over this. I know, I know how appealing it is, to work until you can’t, to let go and make all your thoughts and ideas someone else’s problem, but it’s not worth it. It’s not worth you, Al.” She opened her mouth to continue, but stopped, and awaited a response.

Despite his recent behaviour, his attention stayed locked on her until she stopped talking. Several seconds passed. He coughed lightly, then, slowly, Al began to nod. He turned the rest of the way around, and looked over her shoulder, to the ticking digital clock on the stove.

3:22

He smiled a little. “Alright. Alright, I won’t. I’ll take breaks, and eat, and drink, and sleep.”

She smiled back. “And go outside?”

He turned back around and watched the snow swirl past the window and slip silently to the ground. “We’ll see.”

Ch4

He stretched his hand out towards the top of the tree, where the trunk split to many branches. The oak leaves created a green bubble at the focal point of the branches. It seemed like a buoy, floating three persons’ lengths above the ground. He wondered what it would be like to float, if it would feel liberating, or terrifying, or both. He wondered if there were any experiences in life that might compare.

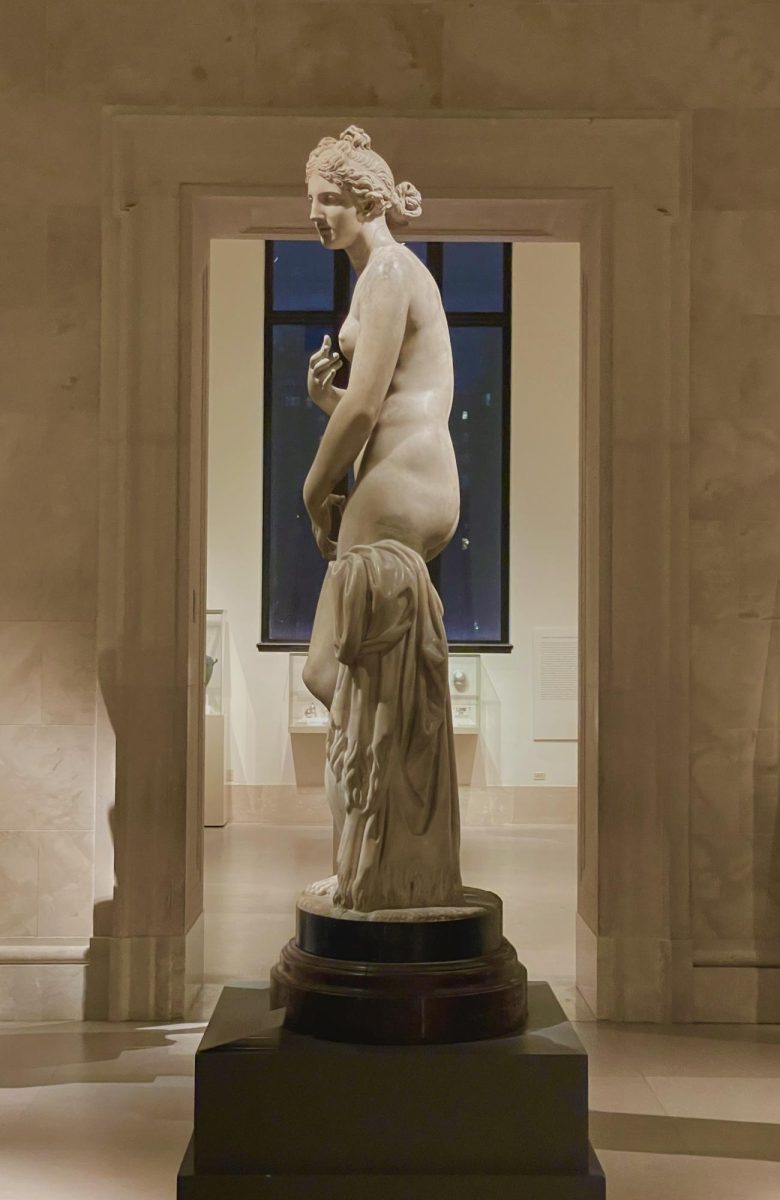

He turned his hand, and stretched it towards the sky. He felt its weight running down his arm and into his shoulder, where it was held in reserve. He curled his fingers, felt the muscles stretch and wind and pull all together. It reminded him of the wonders that had been carved from marble, and how seemingly animate forms could be created from most inanimate stone.

He let his arm drop. From shoulder to elbow remained elevated, but from there it loomed down over him, the tip of his fingers scraping against the ground. He felt the blades of grass pressing into him, the moisture under him, left there by the clouds over him.

A flapping broke the silence; first as if from the distance, then close. A dark shadow broke into his vision, swooping in at the tree, a missive of night imposing itself over the clouds of day. It fluttered, the shape of it seemed to blur and lose focus, then it settled on a branch of the great white oak. It screeched, and pecked the branch upon which it rested, then burrowed its beak into the great black gouts of feathers that sprung up around its neck.

To Al it seemed like spilled black ink on the colourful world around it. It seemed dolorous, as well, as if it had come bearing bad news. Looking at it, he felt the slightest scratches of dread around his psyche, itching and burrowing their way to the forefront of his thought. He was not in his own thoughts though. What occupied him was the world around him- though not in its present form. Instead, he imagined how he may convert it to prose, to allow an interested other party to observe the world through his eyes. Most of all, he wished to allow Sophie – to whom he felt a modicum of devotion, on account of her companionship and patronage of his internal world – to see through his eyes, and think how he thought, and truly understand what is meant to be him. If he could achieve this, he felt he must be happy forever, for lack of any other possible outcome.

He was laying in a park, on a shallow hill. At the top of the hill were more trees, but the one tree he was then observing was some distance away. He had nothing between him and the moist ground, but to his side laid his red, ring bound notebook, and a generic pen. He had considered using a pencil, but feared that, in a moment of weakness, he would erase all his hard work. It had proven to be the right decision; already, he had been tempted to do so, and had the distinct sense that, had he brought a pencil, his day’s work would have ended up erased.

He was trying to find the words to describe his dreams- now and again he’d feel that he knew all the perfect words in all the right order, but by the time he had reached his notebook and been able to write, the sensation had always disappeared, as if it itself had been a dream. The first writing session exempted. Then, and apparently only then, by some combination of the vivid, primal nature of his then most previous dream, and perhaps some milestone of the volume or accuracy of the figments of his dreams with which he surrounded himself, only upon waking from that dream had he finally had the clarity of mind to write with distinct purpose – indeed, it had seemed that he was not creating, but remembering some masterwork of a past life. All his writings since then had seemed but relatively poor writings, merely standing in imitation of a past monolith.

It was, unsatisfying.

Thus, he found himself outside, laying on a shallow hill, in some park that’s name he couldn’t remember, seeking inspiration, to once again write prose deific, to be recited in hushed tones by people in the distant future, and from there the distant past. Most of all, to be met with praise by Sophie, whom, above all, he sought to please.

The rook screeched again. Al could have sworn it was watching him. If anything, with one beady eye turned towards him, it seemed to be taunting him.

Why can’t you write?, it seemed to screech. So weak are you, that you must be literarily provided for by dream, which you are only able to see through apparent whim of happenstance?

It reminded him of something. He didn’t know quite what.

You must be.

He could have sworn he had seen it somewhere. He thought he knew it well.

You must be.

Somewhere. Where, where?

You must be.

He fixated on the black shape in the trees. It had burrowed its way into his mind, in which now it flapped and screeched on its own device. He clenched and unclenched his fists, then, and as he had laid down the notebook and pen, now he picked them back up, and resumed his labour. Now again, as with the first time, prose seemed to appear with little prompting, as if it wanted to be written.

As the crow picked itself up from the tree and began circling above, he felt pleased, in some little, goblin-esque part of his psyche far away from his consciousness, that he may hope to please Sophie.

—

He found himself once again walking down the same road as before, with the pub, the wind, and cars, though now under the weight of newfound snow and ice, the pub less half-again full, and more half empty. All its current patrons sat inside, save for a few brave souls who were willing to drink outside, leaving space for others to sit by the fire within.

There was a deep fog clinging to the ground, rising to just above the height of an above average height person, before slowly fading to nothingness. Beyond some couple dozen metres, only colours and broad shapes were visible, and some few more dozen metres past that, the world seemed to de-corporate. As far as he was concerned, the end of the world was a stone’s throw away. It didn’t bother him though.

A red spectre stood down the road, on the other side. A car passed, again, and through the swirl of parted fog that only held briefly, he saw a familiar storefront, filled with strangities and knick-knacks in no particular order. The sight made his breath catch in his throat, and his heart beat a little faster. He walked across the road. He had an urge to see it again. The walk up to the store seemed to be miles, though he walked it in but an instant. Soon – though far -, he was once again standing before its door, its proclamation of family owned!”. Though there was no breadth to cover, that moment seemed to last an eternity. An eternity later, in but an instant, the door swung open. He hadn’t even been aware of his hand held against its handle, nor indeed the rest of his body. In that moment, it served only to move his eyes from outside that shop to inside. Around him, again, was that most familiar interior. The smell of garlic and sunlight permeated him. He began perusing, searching for what called him. The stacks of books, rows of somethings and nothings. In the corner of the room, a stereo played fur elise quietly. Nothing he saw seemed to jump out at him – interesting stuff, but definitely not what had called him in. Eventually, he ended up back in front of the rack of postcards.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Mercer Island High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.