I love where my parents came from.

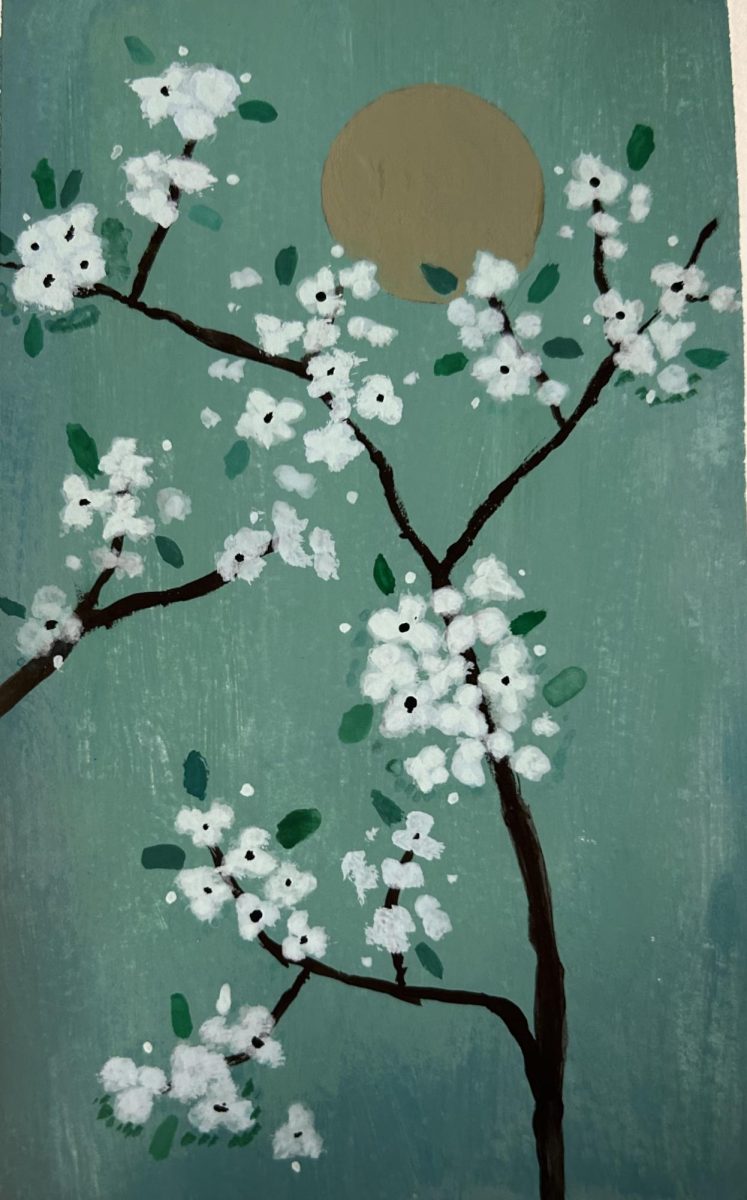

They passed it down to me, an antique pride born from old poets and emperors. Stories of old, of heroes and goddesses in flowing traditional dress. Sun Wukong and Chang’e, Mid Autumn Festivals, New Years, Dragon Boat Festivals: I loved them. I was always the first in traditional garb, first to make dumplings, first to sing to welcome in springtime. I wanted to be Chinese, more than anything.

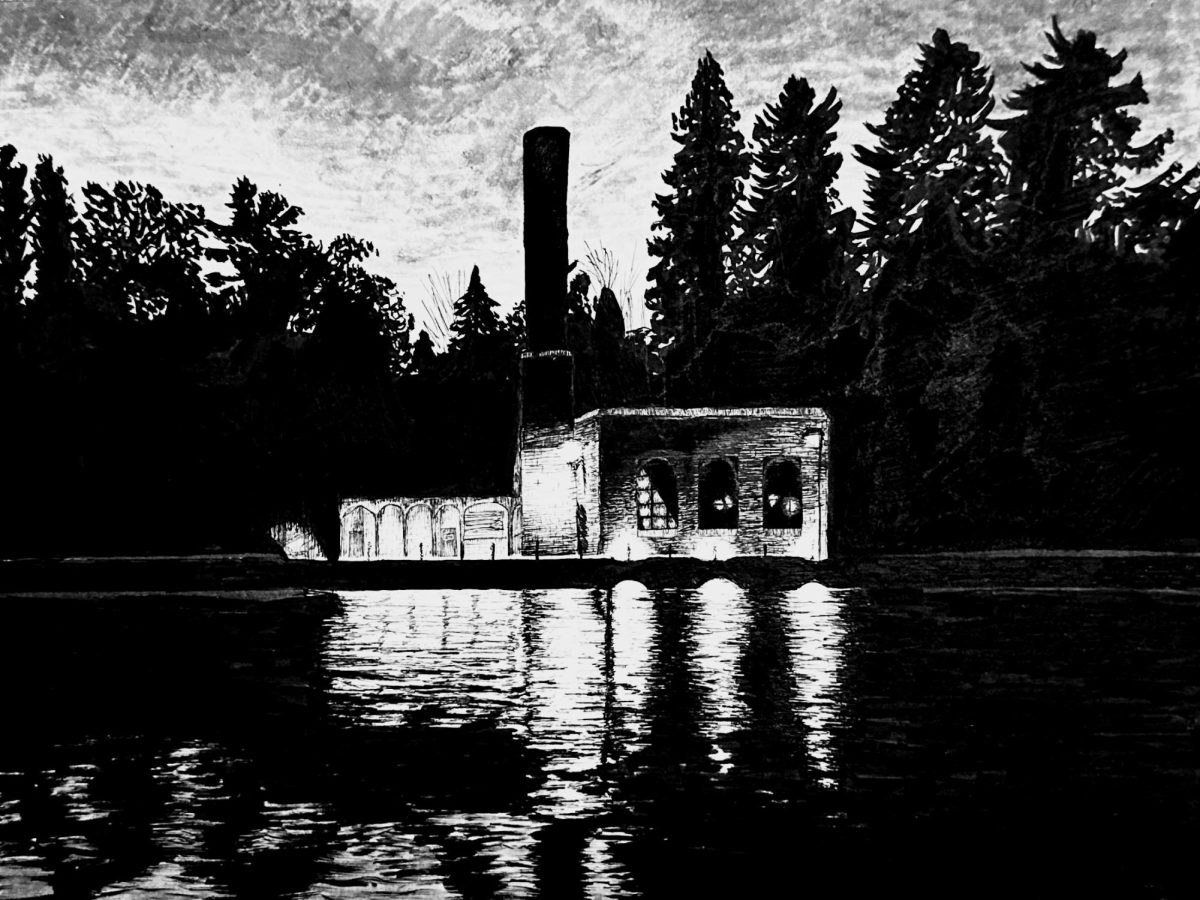

I don’t love where Madison Liu came from. Born and raised in Madison, Wisconsin.

There, it was rolling hills and wheat fields. There, it was English everyday. There, it was “Wait, your last name is Liu? Should’ve been Wisconsin”. There, I was not Madison, the Chinese diaspora, I was Madison the model American kid. Madison Liu from Wisconsin didn’t really care that she was slowly killing that precious inheritance. Madison Liu from Wisconsin just wanted to play with her friends.

Madison Liu stopped speaking Chinese for four years, between the ages 10 and 14.

My mother and father didn’t expect too much from my brother and me. My mother came from a family of teachers, my father lost his dad at 14. They just wanted us to go through the school system and survive, for the most part, nothing as exceptional as shooting for a PhD in another country like they did. They knew what expectation did to kids.

They did, however, expect us to be Chinese. It’s not just speaking the language and making good food (though, I did learn both); it’s filial piety. It’s servitude to your community, it’s trying, even when you fail. Most of all, it’s unshakeable pride. And testing it.

Being Chinese means that your family pokes fun. At others, at you, at whatever. Everyone gets verbally jabbed at one point. My mother tells me a good friend of mine should’ve practiced his violin more before the performance. My father points out a stranger’s “bold choices” in fashion. With their powers combined, they would laugh as I mispronounced the word for “fish” into “jade”.

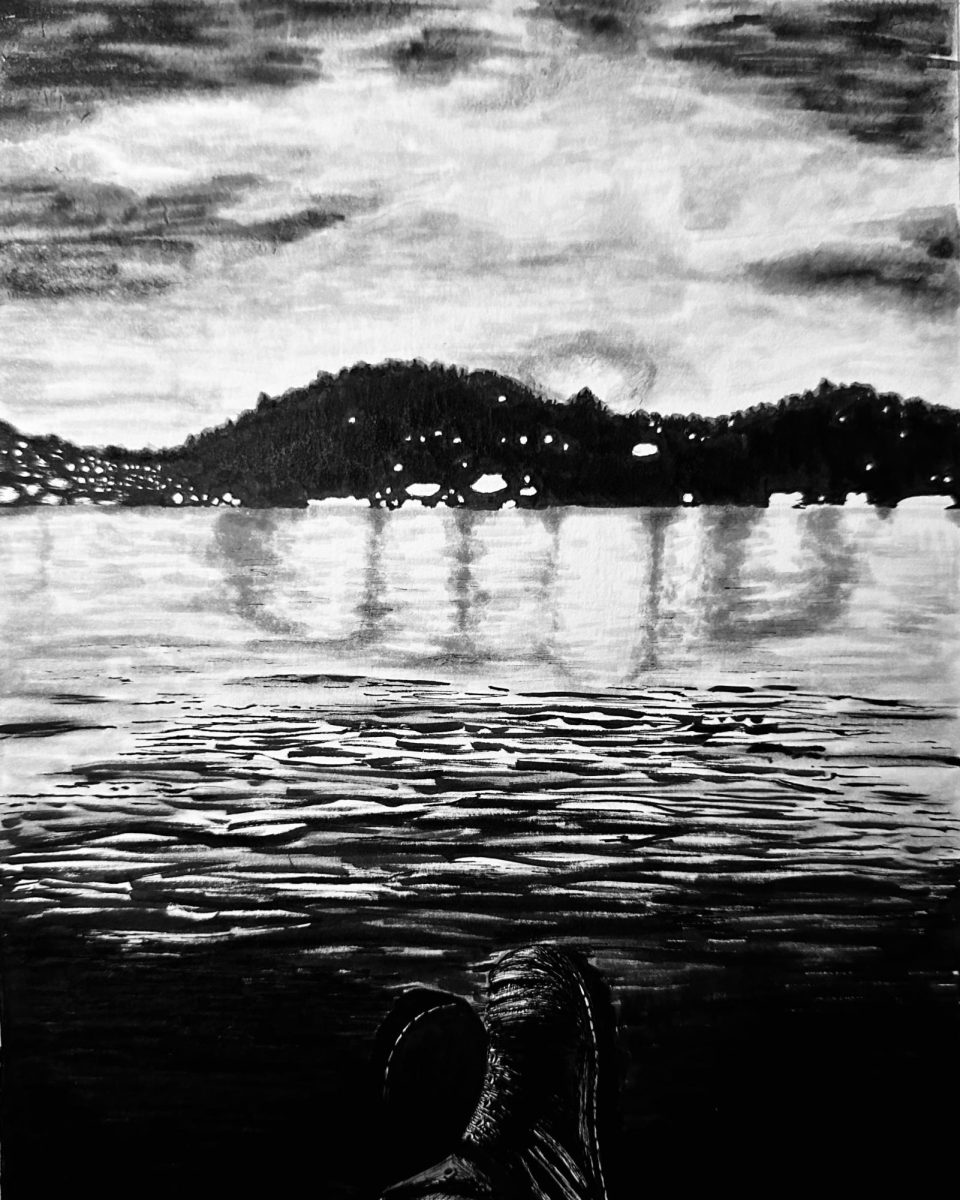

Despite the fact I was always sensitive, I toughed it out. My pride is more like loose gravel than a solid iron fist, there was a lot of it but easy to kick aside and stomp down upon. So it is a bit impressive that I still managed to keep a fraction of my ego, holding onto the truth that I am strong and creative, that with enough time, money, and skillful planning I could do whatever I wanted.

But my one weak spot was always the language. Always, always it was the language, the diphthongs, the stroke order, radicals and poems. My God, the poems, memorized and performed at every Asian kid’s personal hell, language school on Sundays. I think the language school organizers personally sought out the worst and most vitriolic Chinese adults to care for and nurture bright eyed 6 year old innocent Chinese children. Those bloodhounds combined with my family who already liked picking on the youngest, they killed that language inside me. They killed it. That’s how Madison Liu stopped speaking Chinese for four years.

I’ve grown older. Time softens old hurts, there were other things that took precedence. I started speaking Chinese again, isolated during three years in quarantine. It stuck around even after I came back, albeit fragile, scared. I took two exams to prove that language wouldn’t leave again.

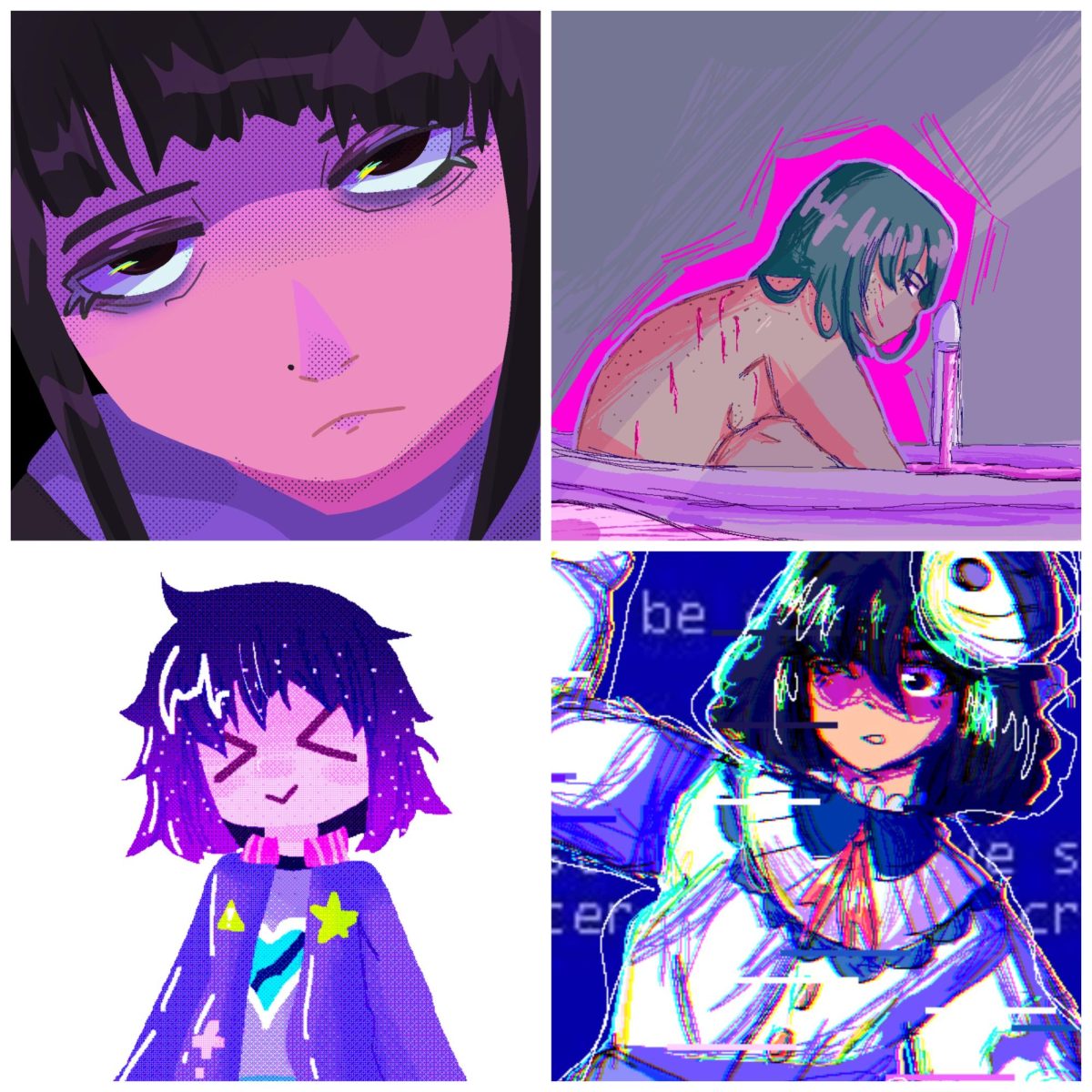

It’s easy to say that I’ve gotten over it, or I’m still stuck in that self doubt. Reality speaks otherwise, though. Drawing Chinese people and writing stories about my culture, does it make me Chinese? Speaking Mandarin, reciting poems, does that really prove anything? Am I a foreigner intruding or am I my parents’ child?

I don’t know. I am still trying to find where I stand in all of this.

I’ll just keep speaking Chinese in the meantime.